Ahmad Jamal and the power of refusal

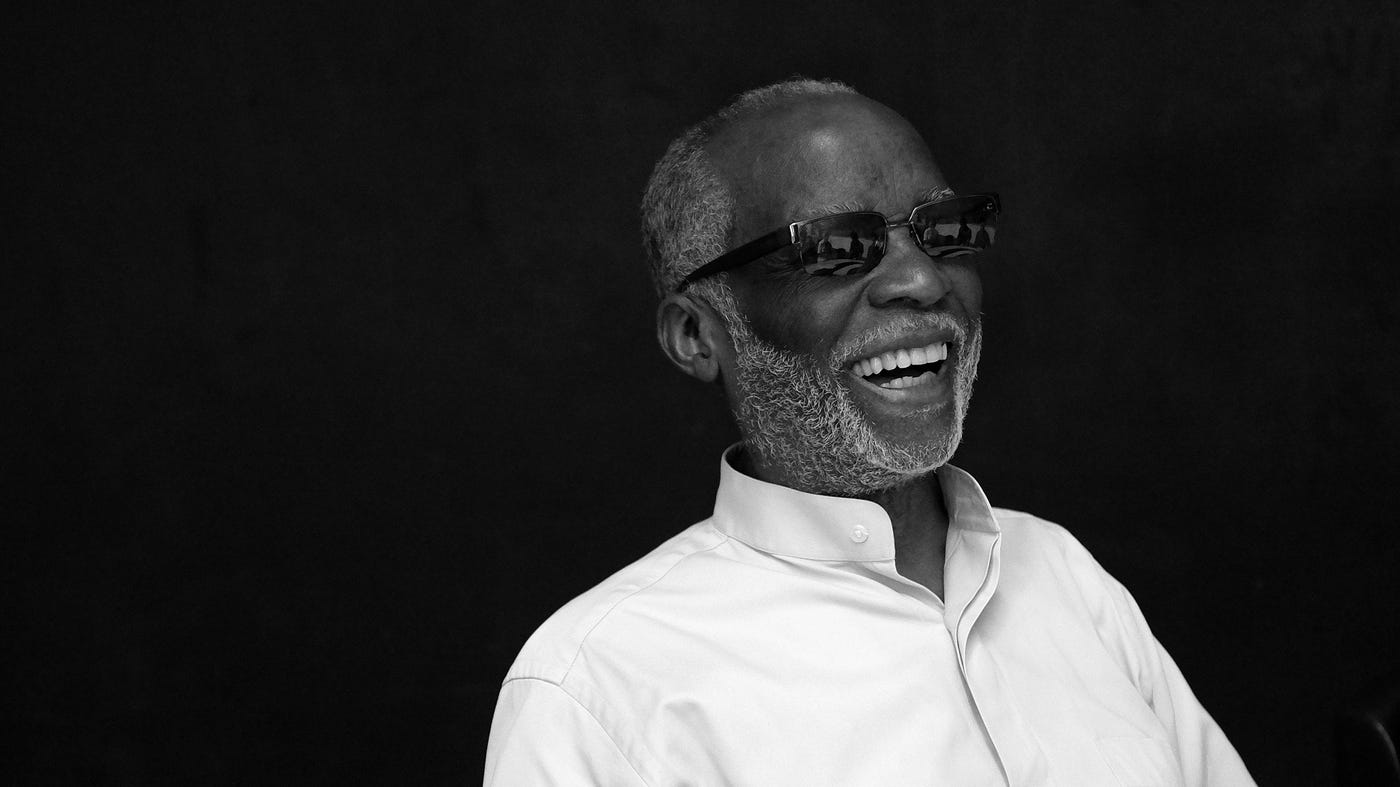

The genius pianist and composer defined every facet of his art, and his arc.

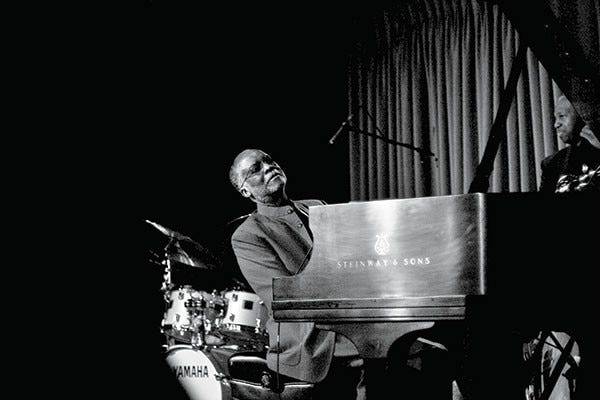

Ahmad Jamal — piano miraculist, dynamic mastermind, supreme orchestrator — died on Sunday at 92, after a battle with prostate cancer. For many admirers, he will always be synonymous with a groove: the terse yet buoyant evocation of New Orleans second-line rhythm on “Poinciana,” in the version he recorded with Israel Crosby on bass and Vernell Fournier on drums on Jan. 16, 1958. Others will reach first for his 1970 studio album The Awakening, with bassist Jamil Nasser and drummer Frank Gant. Wherever you drop in on his body of work, spanning a magisterial 70 years or so, you’ll find a balance of elegance and exuberance, keenness and composure.

I saw the news in my social media feed shortly after coming home from an afternoon concert: Aaron Diehl, playing Mary Lou Williams’ Zodiac Suite with The Philadelphia Orchestra and featured soloists. I’ll have more to say about that musical experience another time; for now, I’ll just say that the pristine clarity of Diehl’s pianism has always called Jamal to mind, among select others. (He happens to play “Seleritus,” a classic Jamal tune, on a new Tyshawn Sorey Trio album due out in June.) And without belaboring the point, Williams’ original Zodiac orchestrations imparted a faint echo of albums like Jamal at the Penthouse, though with clearly loftier ambitions.

Point is, I felt I’d already been communing with Jamal’s sound in some way. And I knew he’d been ailing. Still, the fact of his passing was tough to process. I last spoke with him in September, for a feature on NPR, and he was gracious and alert in conversation. As it ran on Morning Edition, the story used a pair of spectacular archival releases — Emerald City Nights: Live at The Penthouse, in two volumes — as the pretext for an appreciation. Basically, I wanted to give a living master his flowers. I’m proud of the piece, including the host intro, which begins: “Few musicians have stood at the top of their field longer than pianist Ahmad Jamal.” Listen here:

In preparation for this piece, I spent a lot of time mulling over Jamal’s legacy. He has been a core part of my listening, of course, for decades. I’ve reviewed him in concert a few times. But stepping back and really meditating on his career, I was struck anew by something I don’t think gets emphasized often enough: to a truly exceptional degree, Jamal set his own coordinates as an artist, making the music he wanted the way he wanted, and never conforming to any other ideal. Consider this: can you name a record where he appears as a member of someone else’s rhythm section?

I’d be happy to hear from an indefatigable jazz researcher like Lewis Porter, but I am not aware of such a record — an exceedingly rare distinction for a jazz pianist. (Even Erroll Garner, a Jamal lodestar, can be heard comping behind Charlie Parker.) This speaks not only to Jamal’s precocity, or the freedom that comes with a hit record, but also to the purity of his convictions — and a willingness to test the power of refusal.

His name is a key manifestation of that impulse. This fine Washington Post obit, by Gene Seymour, refers to a quote Jamal gave Time magazine in 1959: “I haven’t adopted a name. It’s a part of my ancestral background and heritage. I have re-established my original name. I have gone back to my own vine and fig tree.”

The repudiation of a birth name that he saw as a yoke of oppression was in tune with both an upwelling of Black pride and the tenets of his Muslim faith. And this is a conceptual leap, but when Jason Moran posted a tribute on Instagram this week, he recalled the first time he saw Jamal perform, witnessing “Ahmad’s groundbreaking approach: future-phrasing.” More than a point about the placement of rhythmic emphasis, Moran’s nodding here in the direction of Afro-Futurism, which we more naturally associate with Sun Ra — another pianist-composer who spent key years in Chicago, reclaimed his origin narrative, and forged his own path forward.

When we talked, Jamal knew we would focus on Emerald City Nights — but I wanted to use the album(s) as a way into a larger conversation about his legacy. These recordings from The Penthouse feature him at the helm of several unsurpassable trios, including the one with Nasser and Gant. (Fournier makes a memorable cameo.) So I wanted to ask Jamal what he thought about his stature as a prime architect of the piano trio. In the most fascinating way, it turned out that I was asking the wrong question. Answering it, Jamal provided a gemlike insight onto his musical concept.

I’ll take this moment to express my gratitude to everyone who subscribes to this newsletter. For those who support The Gig as paid subscribers, this post continues with audio of my recent interview with Jamal, and a reflection on what it means. I’ll also consider how the reception to his music connects with a theme in my previous installment of The Gig, “JazzTimes and the White Critics.” (It’s emblematic, really.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Gig to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.