Remembering Roy Hargrove

Five years after the trumpeter's passing, a lively panel and a new release.

Roy Hargrove, an incandescent trumpeter who blazed a new path for his jazz generation, died on this day five years ago. He was 49. A lot of people I know can recall where they were when they got the news. For me, it’s an indelible memory: early the morning of Nov. 3, a Saturday, I woke up in a Seattle hotel room to a text message from Amy Niles, then my boss at Newark Public Radio. “Did Roy pass???” it read.

Still half asleep, I struggled to process the fact of his death, the utter sadness of it. Then instinct kicked in. There were calls to be made, and work to be done. I reached his manager, Larry Clothier, who also seemed to be still processing; he mentioned how strong Roy had sounded in Europe just a week earlier. I notified my editors at NPR Music, drank some coffee, started writing. Here is the NPR obituary —my best effort, under the circumstances, to put Hargrove’s marvelous achievement in context.

Writing the obit consumed the morning and part of the afternoon, and when I finally left my room, it felt like emerging from an awful hibernation. That evening I had a reading at the Elliott Bay Book Company, part of the Playing Changes book tour, and I resolved to make it all about Roy. What I remember most about that evening is the raw emotional catharsis, my voice shaking a little as I described what an important catalyst Hargrove had been, and how much he meant to the scene.

I mostly read from Chapter 9, which bears the title “Changing Sames,” and opens with a reflection on the Soulquarians and their turn-of-the-century rhythm revolution — the neo-soul alchemy that yielded D’Angelo’s Voodoo, along with albums by Erykah Badu, Common and Bilal. (Part of this chapter was excerpted in the NY Times before the book dropped.) I leaned into the moments that feature Hargrove, including what he said during our only lengthy interview, in a back room at the original Jazz Gallery on Hudson Street, which he helped establish and literally treated as a second home.

Throughout the reading, I paused to play music from Voodoo and Hard Groove — Roy’s first album with The RH Factor, born of the same neo-soul intentions — as well as tracks from his quintet album Earfood, and the all-star group Directions in Music. The whole evening provided a much-needed feeling of social connection. I was surprised at the reading by a high school friend who showed up with his family, and also by the parents of trumpeter Riley Mulherkar, who makes a cameo elsewhere in the book. Afterward, I had drinks with Natalie Weiner, who was in town catching up with Seattle friends, and whose admiration for Roy runs seriously deep.

As with any major artist snatched away before their time, Hargrove has inspired some lovely tributes. My personal favorite is “Roy,” an elegy by Ambrose Akinmusire, one of the many trumpeters who regarded him as an encouraging big brother. A 2021 edition of Emmet Cohen’s livestream included this homage, with Giveton Gelin on a Hargrove tune. Gelin is a young trumpeter that Roy took under his wing; like many others, I first heard him standing in for his mentor at a jam-packed memorial tribute on the 2019 Winter Jazzfest, hosted and partly organized by Jazz at Lincoln Center.

A few weeks ago, that organization’s Blue Engine Records released a concert album of The Love Suite: Mahogany, which Hargrove premiered at Alice Tully Hall in 1993. This was a Jazz at Lincoln Center commission, and the music is a flat-out marvel — maybe the most vivid example we have of Roy’s ability to marshal hard-bop fire in a new form, steeped in swinging tradition but sparking and crackling right now.

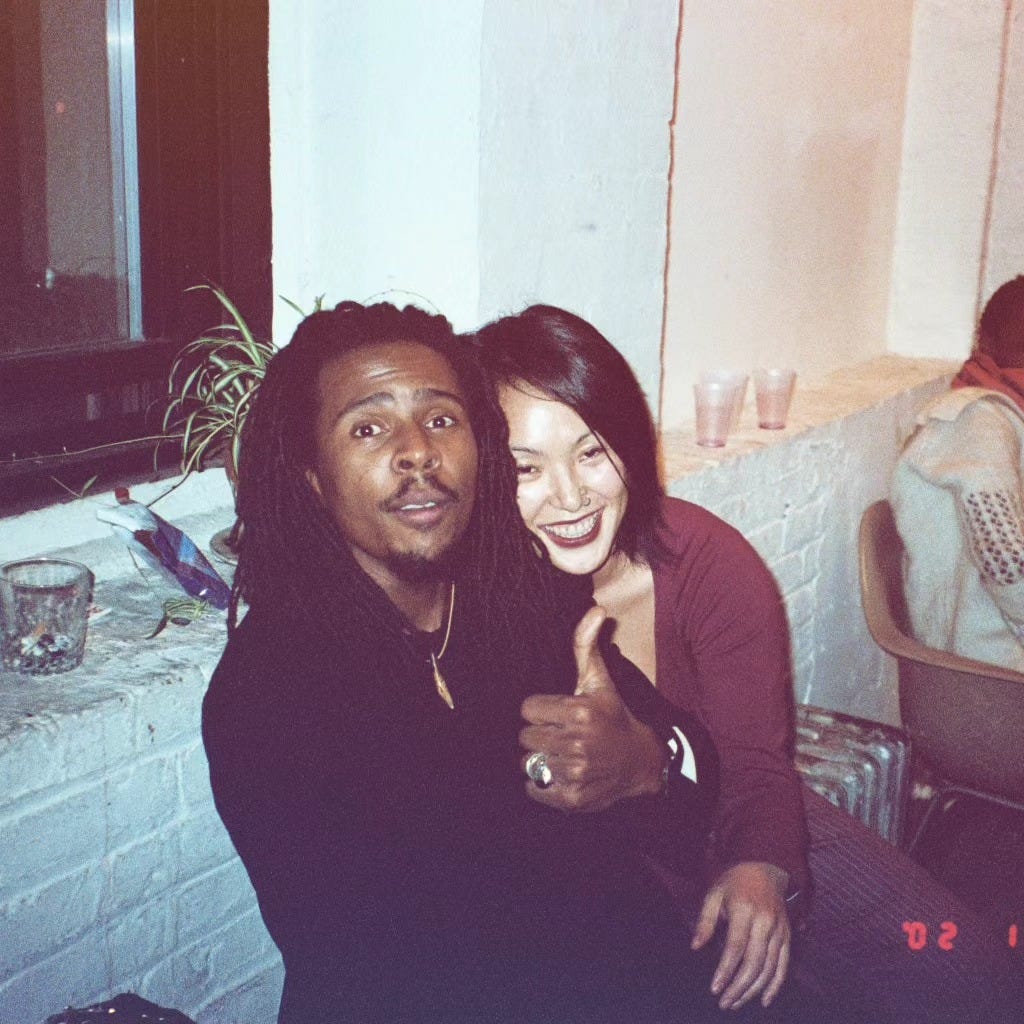

To bask in the wonders of this album — or in any of Hargrove’s music, really — is almost to second-guess the fact that he’s really gone. The other day I exchanged emails with Jonathan Chimene, a former colleague who was gracious enough to share the photo at the top of this post. As a longtime fan and a board member at The Jazz Gallery, Jonathan spent plenty of time in Hargrove’s presence. “I keep expecting to see him walk into a club late at night, holding his horn,” he wrote.

I also spoke this week with Rio Sakairi, The Jazz Gallery’s valiant Artistic Director and Director of Programming, who got to know Roy about as well as anyone. She learned of his passing via text message too. Hers came from Orrin Evans: “Are you OK?” Reflecting on Roy’s long, difficult history of health problems and destructive behavior, she says one of her first thoughts was: Wow, he finally succeeded.

Maybe that sounds a little harsh, but Rio bore witness to so much self-inflicted pain over the years that she had grown accustomed to near-misses with the reaper. Hargrove was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease decades before his death — a condition that required regular dialysis, and was worsened by his drug and alcohol use. “He had no regard for anything besides his music,” she recalls.

In a blog post she published late last year, Sakairi writes: “It was like Roy could not fit into the container he was given and it kept malfunctioning. People who were close to him picked up the slack and patched him up the best we could.”

What occasioned that blog post was the subtext of a documentary film called Hargrove, by Eliane Henri. In the film, the aforementioned manager, Larry Clothier, comes off as a paternalistic enabler who profited not only from Roy’s extraordinary talent, but also from his hapless indifference to practical matters. The specter of race looms, given that Clothier is a white manager with a brusque demeanor. But to hear Rio tell it, Clothier and another trusted member of Roy’s circle, Dale Fitzgerald, put in so much thankless effort just to keep him alive and going. This is a complicated story, because Roy Hargrove was a complicated person. I encourage anyone interested in these tensions to read Sakairi’s post, and consider it in light of Henri’s film.

Hargrove screened at the 2022 North Sea Jazz festival, and when I was asked to put together some discussions, I took the opportunity to convene a panel about Roy’s legacy. Henri was on the panel. So were bassist Christian McBride, who first met Roy as a teenager, and pianist Robert Glasper, who was in his early 20s when he joined Hargrove’s band. (Erykah Badu had committed to join us, but her flight into the Netherlands had been delayed, something I learned after the fact.)

The setup for these jazz talks at North Sea Jazz, at least that year, was supercasual: some benches and chairs on an outdoor stage, next to a wine garden raucous with bar talk. Before the panelists arrived, I worried about whether they would be put off by the informality — so I quickly decided to make it work in our favor. As each person rolled up, I took their drink order, and then rushed over to the bar. This worked as I hoped: from the jump, the panel felt loose and unguarded, like an actual hang. There were laughs as well as catch-in-the-throat moments as we all remembered Roy.

If you support The Gig as a paid subscriber, you’ll find the full audio from that panel below. It’s a conversation that touches on Hargrove’s early renown as a wunderkind; his knack for finding trouble, and the charm he used to get out of it; and the way he straddled eras and ideologies in the music. As Glasper puts it: “He had the gift of being an old soul, but also being fresh and new at the same time.” (Anybody who knows Glasper will get a laugh from the fun he has at my expense.)

I daresay even a hardcore Hargrove-ologist will encounter something new in this convo. “There are probably no Roy Hargrove stories I could share with you in public,” McBride says at one point, though he goes on to tell one. (A damn good one, too.)

Later on, McBride recalls his reaction to the terrible news. Like Sakairi, he’d seen Roy under all manner of physical duress, fearing for his life more than a few times. But he’d always rally. So when he died, McBride recalls: “Part of me wanted to feel relieved because he didn’t have to struggle anymore — but he had fooled me so many times, I thought, ‘Ah, you son of a bitch, you finally did it this time.’ You know?”

Tonight, a legacy edition of the Roy Hargrove Big Band will perform at The Jazz Gallery, with Freddie Hendrix and Duane Eubanks in the trumpet section. If you’re not in New York or just can’t make it out, know that each set will be livestreamed. I should also note that Glasper is at the Blue Note this week, though his full run is sold out; he’s playing this weekend with Black Thought, Derrick Hodge and Jahi Sundance, and there’s no question Roy’s spirit will be moving through the room. (There’s a really beautiful story in the panel about the last time Glasper played with Roy.)

Thanks for reading The Gig. If this is your stop, I hope you’ll put on some Hargrove in his memory. And please share this post! I appreciate your support in any form.