Late last month, to mark the Sarah Vaughan centennial, NPR’s Fresh Air ran an eight-minute tribute by its resident jazz critic, Kevin Whitehead. Part profile, part listening guide, the piece was classic Whitehead: conversational yet commandingly insightful, with each musical cue serving an illustrative purpose.

He plays an early version of “Lover Man” with Dizzy Gillespie, and notes how “at 21, Sarah Vaughan was still developing her gorgeous vocal timbre and exquisite control of her pitch, dynamics and vibrato. Her manner was rough when she started out, but within a few years she acquired an air of sophistication, and absolute confidence in her ability to swoop and plunge at will.” Then comes another recording of “Lover Man,” made nine years later — a natural point of comparison for listeners, a primo A/B.

A moment later, Whitehead reflects on Vaughan’s grudging attitude around certain pop songs, setting up her attempted sabotage of the Bob Hope tune “Thanks for the Memory” from After Hours at the London House. Playing her passive-aggressive scat outro — “Da da-da da-da da, I’m so glad that it’s over,” she sings — he then re-enters as our deadpan narrator: “Her label released that mess anyway.”

There’s more where this came from in the piece, highlighting the armchair ease of Whitehead’s erudition on the air. If you listen all the way through, you’ll arrive at a special note from Terry Gross, the legendary host of Fresh Air, who divulges that Whitehead has decided to step down from his role as the show’s jazz critic — a decision, she adds, that she and others begged him to reconsider. “In the world of jazz criticism,” Gross attests, “Kevin stands out for his deep knowledge of jazz history and his excitement about new performers, including from the jazz avant-garde.”

If you know Whitehead’s work at all, this observation has the absolute ring of truth. Take this review of Multicolored Midnight, a 2022 album by Thumbscrew, featuring guitarist Mary Halvorson, bassist Michael Formanek and drummer Tomas Fujiwara. “Halvorson combines a traditional jazz guitarist’s pick-heavy attack with sparing but pivotal use of electronics,” Whitehead says, “to bend pitches and to split certain notes in two, as if they’re shedding unstable subatomic particles.” Then we hear a full 45 seconds of an effects-laden Halvorson solo. I can only imagine how much the description induces a novice listener to lean in to the strangeness.

As you know, I’m a true believer in the importance of jazz criticism. Often the discourse around it privileges print, and we forget how effective it can be on the radio. Through a huge array of affiliate stations, Fresh Air reaches 5 million listeners every week. Whitehead has been its resident jazz guru since Sept. 1987 — that’s more than 36 years, which exceeds the iconic run Gary Giddins had at The Village Voice.

Remember, too, that Fresh Air goes out to many listeners who have a wary or tentative relationship to improvised music, which made Whitehead a kind of concierge — and as far as I can reckon, the last jazz critic of his stature with a permanent perch in legacy media. The show has said it will bring in a replacement, which is excellent news. But there’s no doubt Kevin and his expansive understanding will be missed.

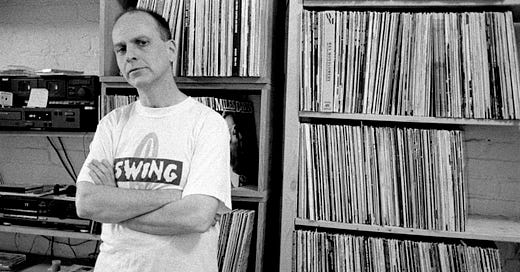

So I decided The Gig would be the perfect place for his exit interview. We spoke over Zoom last week — Kevin from his home in Baltimore, myself from Philadelphia, where Fresh Air is produced at WHYY. It was a fun and deeply fascinating conversation, as you’ll see in the Q&A below (which I showed Kevin in advance, so he could make a few small tweaks for clarity).

Before we dive in, one more note: you can also hear the full audio of our interview —and if you’ve ever listened to Fresh Air when Kevin was on, you’ll know why that’s an enticing proposition. The 28-minute recording is at the bottom of this post.

A Conversation with Kevin Whitehead

April 2, 2024

Nate Chinen: Kevin, the first thing I have to say is congratulations, because this is really an epic legacy. It's a remarkable tenure in one place, and a really wonderful body of work.

Kevin Whitehead: You know, when I was a young freelancer, I developed the idea that for any good gig you get, anything over two years is gravy. So this one has been kind of amazing, to think that I would wind up doing it half my life.

NC: When you made your announcement, the first thing I thought was, literally, “end of an era.” Then my second thought was: who had a longer tenure in such a visible position, as a jazz critic? Gary Giddins at the Village Voice is really the only person I can think of who was so consistent over such a long period of time.

KW: I have to say, I never really thought of it in those terms. I think of somebody like Paul de Barros, who’s been a jazz critic at the Seattle Times for decades and decades. I’m sure Paul was at it before I got started.

NC: That’s a great point.

KW: But it’s certainly true that when I started on the show in 1987, there were a lot more daily newspapers, and a lot more jazz critics at daily newspapers. So as time went on and jazz critics got fewer on the ground, I began to appreciate more and more what a fantastic position I had at the show, which I already knew was great. I mean, the job just fit me so well, and I think it’s a perfect format for jazz criticism. You know, you have eight minutes to show and tell. You can talk about the music, of course, but you also get to play it for people so they can hear it for themselves and maybe make their own judgments about what they think about it.

NC: Now, you didn’t come from a radio background when you started. Your background is in print, like me.

KW: Yeah, I started writing for Cadence in 1979. And Francis Davis was writing there around the same time. He remembered my writing, and when he started editing the jazz section for Musician magazine, he brought me on as a critic there. Then I was kind of off and running. I did a lot of work for Art Lange when he ran DownBeat in the ‘80s, and that was the place where I really learned how to cram a lot of information into a short space. Because, you know, you’d have 400 words to discuss the complete Ben Webster on EmArcy or whatever.

NC: Right.

KW: So I’d write 500 words and then boil it down. And that proved to be something that really came in handy in radio, because you don’t have all day to talk about stuff. It’s better if you have about as much music as you do talking in a piece.

NC: Was it Francis who brought you aboard at Fresh Air?

KW: The show went national in May ‘87, I think it was. And Francis was the original jazz critic. Probably because he was so busy at that time, and rightly so, he decided it wasn’t a good fit for him. He recommended that they audition a few people, and I was one of them. Somehow I got the gig. I made the audition tape standing in front of the stereo: let 30 seconds of Charlie Haden play, and then I move the microphone to my face and start talking for a little while. Danny Miller, the senior producer, called me up to tell me that I got the gig. He said, “You know, you sounded OK, but you were talking so slowly, it was as if you were addressing a room full of drunks.”

NC: [laughs]

KW: One thing that I should mention about working at Fresh Air is they make it really easy. The process is streamlined to get your stuff on the air without messing with it a lot. They’ll save you from yourself if you need it, but if you do things right, you don’t need it that often.

NC: Sticking to this early timeline: what was your learning curve? If there was any struggle, what did you struggle with, transitioning from writing for the page to writing for the radio?

KW: It’s sort of a gradual process. When I got the job, they sent me a sample review and it was Francis on Ornette Coleman’s In All Languages. And in some ways it’s like a template for everything that came afterwards: 30 seconds of music at the top, and then he gives you some historical background, and he tells you what to listen for in the clip. But then he played an entire piece of music, like a five-minute chunk of music there. When I heard that, I went, “OK, this is how you do it. You set the clip up and then you go.” And the first ones I did were kind of similar; you’d have a huge chunk of music in the middle of it. Then gradually I realized what Francis would have realized if he’d done it for a couple more months: you have to break it up more. So I got it into this dialogue of paragraphs and pieces of music, is the best way to think about it.

NC: Yeah.

KW: And at first, it’s like a print piece that you illustrate. But gradually I realized there was another way to put these pieces together, and that was to start with the music that you wanted to play, and then make a sequence that flows well, and figure out a way to stitch them together, adding information at the appropriate time.

NC: That’s a really crucial distinction, because when I think about your reviews for Fresh Air, I think of you as a curator as much as you are a critic. It’s clear that your musical selections were made with such exacting care, to give listeners the meat of the thing, but also to pull them forward and give them a narrative.

KW: That’s what makes the pieces such a joy to put together for me, is that kind of puzzle. Figuring out the exact 38 seconds or whatever that you want in a piece that really shows something — and then, you give people some kind of orientation to what to listen for. But I really like the idea that a radio piece can have a kind of musical flow of its own, you know?

NC: Yeah.

KW: And I also, again, like that idea that if you play enough of the music, then people can kind of decide for themselves if there’s anything there for them.

NC: Often in public radio, there’s a built-in concern about alienating a listener — you know, sending people to change the dial. And when I think about your voice in Fresh Air, and what you’ve chosen to highlight, it strikes me how free and fearless you’ve been with your choices. The entire range of the music is covered, including stuff that most people would file under the avant-garde. And you do such a marvelous job of highlighting the human stories behind this music, and taking listeners by the hand when it’s more challenging. I have to imagine that there have been conversations over the years between you and your producers over how exactly to make that work, and why it works when it does.

KW: You would think that would be true, but we’ve had remarkably few such conversations. I have to say, I assign my own pieces. I never really get any pushback. It’s obvious that my tastes are a little more avant-garde than the jazz fans who run the show. Every once in a while, my producer, Roberta Shorrock, who I’ve been working with for over 30 years — and let me just say right now, in case I don’t later, that working with her is one of the great joys of my professional life, because she always makes me sound better and knows what to do. She will let me know if there’s something she’s not so crazy about. But nobody ever told me to tone it down. I worry about it myself, of course — because you don’t want to be turning listeners off. And I do notice, I have a tendency where if the music is kind of out, the excerpts will be a little bit shorter, just maybe out of timidity on my part. I gave a talk a few years ago in St. Louis, and there were a bunch of people that were listeners, so I asked them: sometimes does the music get a little strange? People seemed to allow that that was a fair statement. So I said: “Here’s the question: Does it ever get so strange that you turn the radio off?” And nobody said that they did. So maybe that’s a victory.

NC: For sure.

KW: I remember from when I used to listen to public radio before I was on it, not every band that was featured was something to my taste — but I was interested to know what was out there. When I started doing this show, and a few years after, was when the Jazz Wars started heating up; there were people arguing for a narrow definition of jazz, and I was pretty vocally on the other side of that argument. So I think looking back at the stuff that I reviewed early on and afterwards, I always was trying to make a point that jazz is a really diverse field. I tried to kind of open it up at the margins a little bit. So I would talk about, you know, some of the European improvisers and then maybe Julie London.

NC: I’m really struck by the symbolism of that date, because 1987 is the year that Jazz at Lincoln Center is born, and also when the Knitting Factory is taking off downtown. So when you say Jazz Wars, basically your first decade on the air was dominated by that discourse.

KW: Yeah.

NC: It’s always been clear that rather than taking a side, you’ve always been really insistent on this kind of ecumenical — you know, like “All of this is valid and deserves our attention and our time.” That perspective has kind of won the day, and you’re too modest to say it, but I think the work that you’ve done over this time is one reason for that. Just staying the course and sticking up for that perspective, I really believe it’s made a difference.

KW: Well, that's great to hear. Here’s what I’ll say about the Jazz Wars. We don’t talk enough about how the good guys won. If you look at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s programming now compared to the early ‘90s, it’s clear there’s been a substantial shift in the way people look at the parameters of the music.

NC: Yeah, absolutely true. Now, in addition to reviewing albums, you also do things like your final piece, the remembrance of Sarah Vaughan’s entire career. Are there any other special pieces like that you remember fondly — where it wasn’t a single album or body of recordings you were talking about, but something broader?

KW: There was a series that Roberta Shorrock and I cooked up in the early 2000s, “The Avant-Garde Made Easy.” We did six of them. It was like: This music isn't scary, here it is. Albert Ayler, Anthony Braxton, Cecil Taylor, Misha Mengelberg, Lester Bowie, Sun Ra. There was one in the early ‘90s: Why Don't More Singers Sing the Introductory Verse? That was a thing I was on about for a while. Misconceptions About Ellington, around the time of his 100th birthday. And that sort of became a thing in the last few years, now that there are so many centennials. I saw that as an opportunity to talk about people like Sarah Vaughan or Sam Rivers or Von Freeman or whoever. I enjoy doing those pieces because I often try to avoid the standard pieces that you would hear. The Sarah Vaughan piece is a good example of that. You know, we didn’t hear “Tenderly” or “Send in the Clowns,” but some odder material.

NC: That’s one thing I love about everything that you’ve done on the show: your personality and even some of the quirks of your listening are there, but always in the service of the bigger picture. I mean, the Sarah Vaughan piece is kind of a perfect example. It's so easy when you’re talking about a figure like her, or Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington, to revert to a kind of professorial jazz-historian mode, because they are that important. And whenever I hear you talking about a figure like that, it’s more like you’ve got your arm around somebody’s shoulder saying “Hey, let me tell you about this person.” The personality and the storytelling are so clear. It never feels didactic or like an eat-your-vegetables kind of lesson.

KW: [laughs]

NC: You’re a great storyteller, and I think it’s always been in service of the music.

KW: People like a good story, you know. They like a good hook for something, and I’m looking for ways to bring people into the music. But I’m also really interested in the process of music making, and that’s something else that I’ve tried to deal with a lot in those pieces. They’re less about what I think of the music, and more about how it’s put together.

NC: Mmhmm.

KW: I’m trying not to make them about my reactions to stuff, or to be talking about myself. I mean, obviously they're all my reactions because it’s my piece. But I’m using the word “I” a lot more today than I do on a radio piece.

NC: Right. Well, activating listening in your unseen audience is at the heart of what you’re doing, right? So by setting up the clips — by gently nudging someone to notice a particular thing that’s about to happen — these are ways to sort of lead the horse to water, if you will. And especially in this day and age when we don’t have a sort of Leonard Bernstein Young People’s Concerts model in public life, anytime you are able to do something like that on a platform this big, I think it’s really meaningful.

KW: Yeah. Help people learn how to listen. I think that’s what it’s about. If you teach people how to listen to one kind of music, they can apply that to whatever kind of music that they’re more interested in. That’s one reason I would do pieces on stuff like free improvisation, because a lot of times you can actually really hear the process as it’s happening, right? It’s nice to get that stuff on the air sometimes. Everyone should hear Evan Parker once in their lives.

NC: There’s a quote that I’ve been thinking about recently. I was at the Museum of Modern Art, and they had an installation where there were a bunch of old landline telephones. You could pick up a receiver and listen to a recording of an artist reading something. I happened to pick up a receiver, and heard the voice of John Cage reading — I assume he was reading from his book Silence, because the passage that he read was: “Our business has changed from judgment to awareness.” And it struck me like a lightning bolt, standing there with the receiver to my ear. I jotted it down, because it seemed so meaningful, as a critic in this day and age.

KW: [chuckles] I like that.

NC: So this is a long-winded way of coming around to the question of how your work has changed as our field has changed. Because the role of the music critic is quite different today than it was in the ‘80s or even the ‘90s. And I wonder what thoughts you have about that, and how it changed how you operated, if at all.

KW: Things are different in a lot of technical ways. I started talking about this before. When I first started out, I’d go down to the public radio station in whatever town I happened to be in at that time, and I’d bring a copy of the LP, and then I’d record some music and my voice tracks that I’d edited on the phone with my producer in Philadelphia. And then they’d hand me a DAT tape, and I’d send it to Philadelphia in the mail. Lately I’ve recorded in my bedroom closet on an iPhone. The CD was a great invention in terms of reviewing music on the radio. It saved me hours and hours of time, and is the principal reason that I’m not sentimental about vinyl.

NC: Right.

KW: And also, pre-internet, it was understood that a piece that you did for radio, you could do a version of for print also. Which you kind of needed to do, Because when I first started on the show, all the critics were heard once a week. I was on every Monday afternoon. So you were always looking for material. It was about four years later that they let up on us and went to about twice a month, where it’s basically been ever since. Including some film reviews I did back in the day, I think the Sarah Vaughan piece was my 850th piece for the show.

NC: Wow.

KW: So what else is different? You get to the point where the internet is suddenly there, so now there are transcripts online, and there’s much more music available. But in a lot of ways, just in terms of what I do on the program, it was like I had the last 20th-century job. I was still doing it pretty much in the same way. I wasn’t trying to fix what didn’t seem to be broken. The culture of the show is so strong that they have carried on really, really well since I started there. There are so many people who are still working there who have been there for over 30 years. That’s a testament to what a good place it is to work.

NC: That brings me to Terry, and whatever relationship you have with her, personally and sort of psychically, having been on the show for so long. I loved her sendoff, and knowing a little bit about her listening habits, I absolutely believe that she learned from your listening. What can you tell me about the rapport that you developed long-distance with Terry Gross over the years?

KW: She is as she seems: she’s that engaged, she’s genuinely interested in people. I don’t have so much direct dealing with her because she’s in Philadelphia, and I have variously been in Baltimore, New York, Chicago, Amsterdam, Kansas, Texas. I’ve been in a lot of places since I started doing that show. But I would get into Philadelphia every once in a while, and we’d sit and talk a little. Danny Miller, the senior producer of the show, he’s a great guy to work for. Whenever there’s a reason to pat you on the back, he’ll let you know about it. Roberta Shorrock I mentioned before, my segment producer; she’s my Billy Strayhorn.

NC: Yeah.

KW: To work with somebody for 30 years and never have an argument or serious disagreement, and really understand each other and what they’re trying to do? Wow. That’s just an amazing thing. Also the fact that I lived in Holland for four years during my time here, because I wrote a book about Dutch improvised music. One of those years, my participation was so lean that I filed nine reviews. And they still kept me around, for me to come back. I really, really appreciate that kind of commitment.

NC: Yeah. Now, all this time, you never stopped writing for the page as well, and I wonder if you can identify or articulate any way in which your time at Fresh Air influenced your non-radio writing. Was there an impact?

KW: I think in the last few years, more and more when I write record reviews for print, I feel frustrated that I can’t slam a little music into the middle. It's funny.

NC: But is your writing as a critic different because of your time on the air?

KW: It’s probably a little clearer, because you have to be a little clearer when you’re talking to people. As a young writer making the transition from the typewriter to the word processor, every sentence got more and more rococo and ornate, with more clauses hanging off the Christmas tree. And being on the radio helped me pare that back. There was something else that you just said that I think is really important. Not all music works for the kind of reviews I was doing on the show. Music where things change really, really slowly — that does not work so well in that kind of format.

NC: Yeah.

KW: I should probably say also that if the music’s really good, but I don’t really have anything to say about it, I'll probably just leave it alone. Nobody hears everything, let’s face it. We all have our deaf spots.

NC: We’ve alluded to this, but music criticism is pretty disenfranchised at the moment. There’s not a regular reviewer at the Times. JazzTimes went under last year. I’m hard-pressed to think of a newspaper that has a full-time jazz critic. We’ve almost become accustomed to not encountering jazz criticism anymore, which is a shocking turn for me. I wonder if you have any reflections as you’re stepping away from what I almost think of as a tenured faculty position?

KW: [laughs]

NC: You know: what are your thoughts about where we are, in terms of jazz criticism in the public sphere?

KW: Things are grim, there’s no question. There are so few outlets. And yet there are still a lot of writers coming along working some kind of way, Substack or otherwise — I’m looking at you, Nate — who are still carrying on and doing really good work. So in some kind of way, I think people will make themselves heard. How it will happen, I can't say. I’ve read so many critics telling you what jazz was going to be like in the following decade, and they’re always wrong.

NC: [laughs]

KW: So I resolved never to make those such predictions myself. I don’t always honor the rule, but I try. I realize how lucky I am that I have worked for people who are firmly committed to having a jazz critic in place. It really helps to have a show that’s run by jazz fans.

NC: Now, when Jon Batiste was coming in to The Late Show, I happened to do a piece for the Times about it. I talked to Paul Shaffer and asked him: every day at a certain time, are you going to feel a certain twitch? Is it going to be hard to not have this routine? So I’ll turn that question to you: do you feel like there will be moments where you hear a new record and start writing your Fresh Air review in your head, and have to kind of pump the brakes?

KW: It hasn’t happened yet, but yeah, I think that will probably happen. Let’s face it, you don’t retire from a gig as great as this one without having second thoughts about it. But I’m OK, and I’m looking forward to hearing my successor. I don’t know who that’s going to be, but I’m really looking forward to hearing what somebody else has to say in that format, because it’s such a great format and I know it so well. It’s like hearing somebody blow on rhythm changes.

NC: Right. Well, I also look forward to that — but I think I speak for innumerable listeners and certainly a lot of musicians when I say that you will be missed. I didn’t want to let this opportunity pass without giving you some flowers and thanking you for a tremendous service to the music, and an example for those of us trying to write and talk about it.

KW: Wow. You are so very welcome. I’m glad to be of help to the music in any way I can. Also, I should say, everybody’s been so swell giving me a sendoff. I think they’re going to be disappointed when I have a piece on the radio in a few weeks. I thought we were rid of this guy. Why is he still here?

NC: [laughing] No, no. The door’s always open, man.

I hope you enjoyed reading this interview. As I said at the top, you can hear the full conversation, too — and trust me, this is an engaging 28 minutes of audio for anyone with a passing interest in jazz, public radio, or music criticism. Speaking of which: by signing up as a paid subscriber to The Gig, you also support everything I do here.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Gig to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.